In this episode of the Gallery Girl podcast, we are joined by Muriel Ahmarani Jaouich, a Canadian artist of Armenian, Egyptian and Lebanese descent. Her gorgeous paintings illustrate genealogy, intergenerational trauma and historical violence. This sentence sounds like a juxtaposition, how can trauma and violence be beautiful? Yet Muriel’s delicate colour palette manages to bring a softness to a history that is complicated and painful.

Muriel’s lineage has a strong impact on her work. Her maternal grandparents were both orphans of the Armenian Genocide, both hailing from Mardin, meeting each other in Alexandria, Egypt, while her father’s side was Egyptian and Lebanese, with some of her ancestors being persecuted by the Ottoman Empire in Lebanon in the 1880s. Both of her parents were born in Egypt, while Muriel herself was born in Canada. “My grandparents on my father’s side were doing six months in Egypt and six months in Canada”, explains Muriel, “On my mother’s side they left Egypt and went to Lebanon. I still haven’t gone to Mardin, and actually in the last few years that’s something that’s becoming very important for me, and as well to Armenia.”

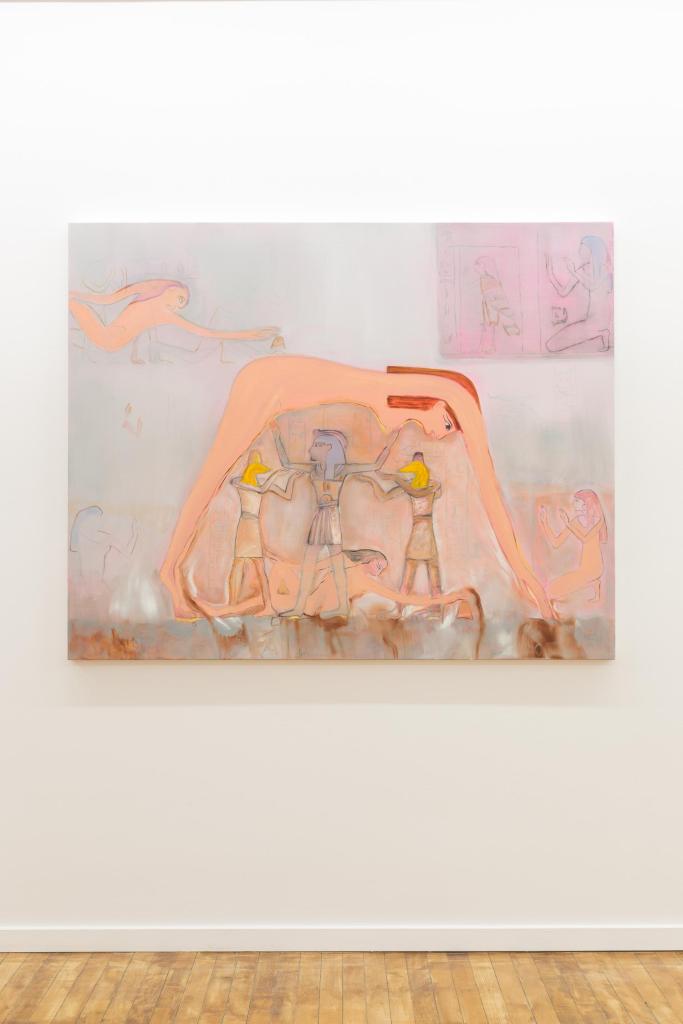

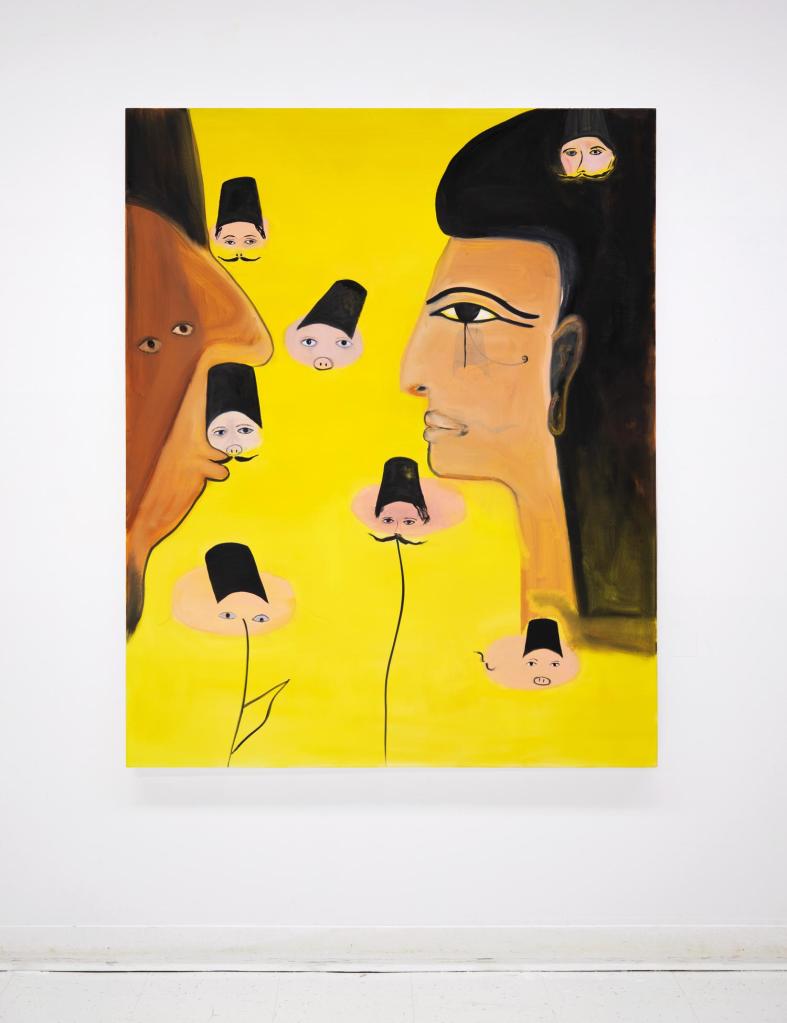

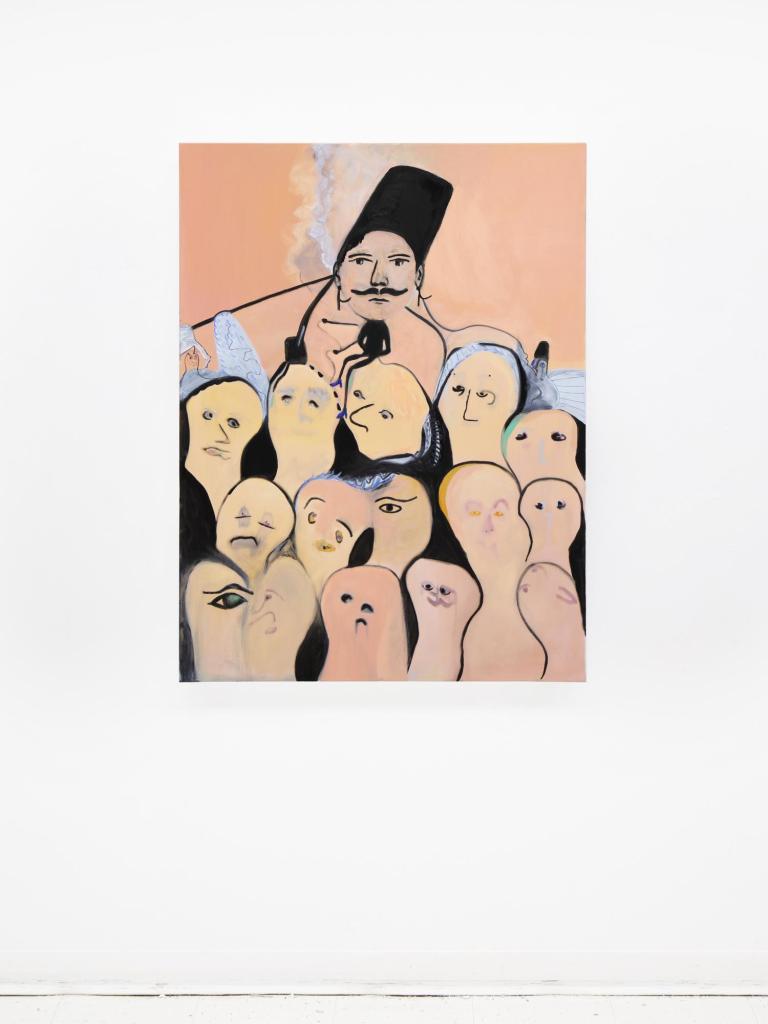

When Muriel started her MFA three years ago, she found that she had been given a container in which to focus on her family heritage. At this same time there was a lot of conflict in Artsakh, which continues to this day and is now under blockade. As a consequence she conducted a lot of oral history research. “Initially I was working a lot with the Armenian Genocide, representing Talat Pasha, the orchestrator of the Armenian Genocide”, says Muriel, “I was going at it from a very raw perspective, delving into the paintings and creating a story with each painting.” During her MFA, her father’s health declined, causing him to lose his capacity to speak, prompting a need to also delve into her Egyptian heritage, implementing Egyptian iconography into her work. “I realised that Egypt was the land where my family on my mother’s side was able to reconstruct their lives”, she says, “It became this safe space from which I can rewrite this story.” As a result, you will see aspects of ancient Egyptology in her work, gods, and pharaohs representing different people in her family within these paintings.

Yet, in spite of this inherited trauma, Muriel’s colour scheme juxtaposes the history she recalls. “I feel that a lot of the work that I’ve been doing has been working to find my own centre and to heal that wound”, she explains “I’m trying to be a safe space for my mother and my cousins. I was really exposed to this fragility. I had this awareness that there is trauma and I want to see how I can stabilize myself somehow to be able to hold it and to be able to speak about it.” Through this process, Muriel has created a sense of softness. “As I’m painting I’m navigating through all of these emotions”, she adds, “For now the way I’m painting is a way to process all of this somehow.” She describes this as exutoire, a French word meaning outlet, or release.

Muriel explains that she had recently discovered that one of her great grandfather’s had been decapitated. She had already illustrated Talat Pasha’s head, reclaiming the narrative in reverse. When asking if she ever wonders what her ancestors would think of her work, she explains that there are a lot of photographs of her ancestors in her studio. “I feel very held by them”, she says “I am often talking to them. In my work, through the act of painting, I feel that is the way I am connecting with them.”

Muriel goes on to explain that with the Egyptian influence there is also a focus on the afterlife. “I have been painting a lot but I’m not an Egyptologist, but I do want to read more.” Within her work she has depicted many ancient Egyptian gods and figures. “There is often the newt goddess, who is the goddess of protection”, she says, “There are definitely some [gods] where I intentionally felt the connection.”

We discuss how many artists with roots outside the West are drawn to illustrate their ancestors. “There is this obsession with youth. I always feel a little disturbed by that. When I think about other cultures there is such a respect for our elders”, she explains “In a lot of ways I find that I can find my strength when I think about my ancestors and what they’ve gone through. All of these migrations. It feels like there is a real attraction to look to them somehow to look for inspiration. For strength. For understanding where I come from. What kind of resilience my people have gone through and survived. It’s extremely powerful.”

Recently, Muriel has had solo shows in both Toronto and New York, allowing viewers to react to her work. “It’s talking about it [the Armenian Genocide] through beauty”, she adds, “It allows me to talk about what has happened and what continues to happen in the region as we speak about Artsakh and Azerbaijan.” She adds that some viewers react to the Egyptian aspect. “It’s like a subversive strategy for me. I can talk about the Armenian Genocide through this Egyptian iconography”, she explains, “I don’t think it would be received the same way if I spoke about the Genocide so directly.”

Besides her heritage, she is inspired by Buddhist philosophy and the unknowing. “It’s creating the conditions where in the silence there is so much that can emerge” she explains, “This not knowing comes from a spiritual perspective.” Muriel also stresses that there is also a financial reality and that she does work part time. “I feel it is important to talk about this”, she stresses, “There is so much precarity when it comes to being an artist. We gain from transparency.”

Currently, she is taking a pause to step back to let things fall and allow other things to emerge. That said, she does add that she hopes that her work gets more recognized in the countries that she’s from. “I would like to connect with the people from my heritage, but more directly than from the diaspora”, she says, “I did have a friend who was sent to Artsakh and who showed my work to a family there on her phone. She sent that to me and they were really moved. That was really special to me.”

You can find Muriel at her website here and her Instagram here